ALIEN OR XENOMORPH: HISTORY, MEANINGS AND SYMBOLS

What is the Alien, or Xenomorph? Let’s find out its story, the meanings and symbols of the scariest predator in the universe. Anyone who has

BLACK FRIDAY 20% – code: BLACK2023 |

Would you like to receive your order by ❤️ VALENTINE’S DAY? Make your purchase by January 25th.

CHRISTMAS CLOSURE🎄- New orders will be processed from 8 January 2023

“The Sirens enchant him with limpid song,

Lying on the lawn: around it is a pile of bones

Of putrid men with wrinkling skin.”

(Homer, Odyssey)

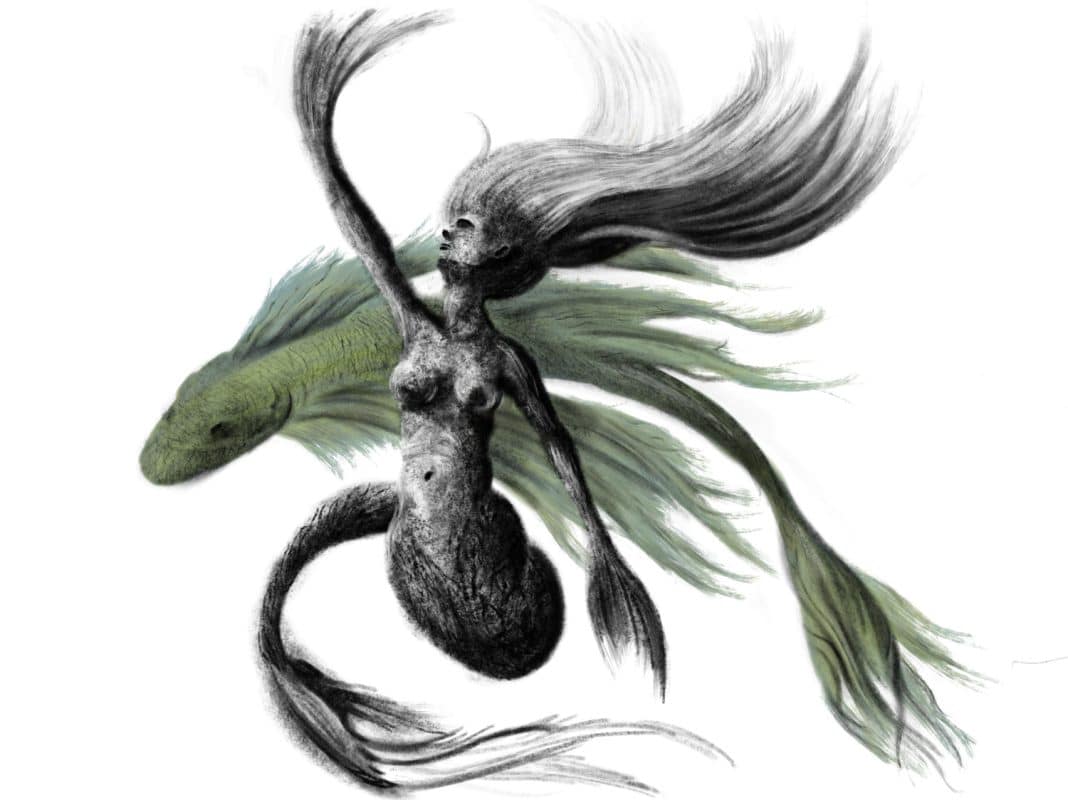

Cruel predators or charming maidens, mermaids populate the art and legends of cultures thousands of years old. Appearing in literature with Homer’s Odyssey, they presumably have a much older origin, linked to oral traditions. Reading the Canto in which Odysseus meets them, in fact, there is no mention of their shape, suggesting that everyone knew what a mermaid looked like.

Half woman and half fish? No, not at all.

Homer’s Sirens were very different and look nothing like the iconography we are used to. If, like me, you are in love with the ancient legends of the sea, amid horrible monsters and wonderful creatures, in the next few lines I will take you among the waters of the European seas to discover a figure as famous as she is unknown and mysterious: the mermaid.

Before we set sail, however, a few premises:

– The mermaid does not have a single form. As I will tell you, the mermaid does not have an unambiguous definition: the creature that animated the stories of the Greeks is not the same one that rested on the rocks of Denmark. Who is right? All and none, of course. A fairy-tale and literary character, he owes his nature to the imagination of artists or the suggestions of sailors.

– Siren has no clear etymology. What does “mermaid” mean? We don’t know for sure. Some scholars speculate that its name derives from the Greek seirà (σειρά) and eírō (εἴρω), which joined together lead to the meaning “rope that holds back,” referring to the power of mermaids to captivate, binding you to them with song. Among many other hypotheses, there are some that see the origin of the term coming from cultures far older than Greek, such as the Sanskrit culture.

– The mermaid has no scientific basis: it is a purely imaginary animal. It is possible, as with other legendary monsters, that the inspiration came from real animals, such as walruses. Water mysteries always offer great surprises to science, but for now the mermaid should be considered pure figment of the imagination.

You may have heard of Ulysses’ Mermaid Island. If you imagine a lot of beautiful maidens with fins, however, you are sadly mistaken. Homer actually gives us no description of sirens, suggesting that the Greeks of the time knew exactly what they were about. Depicted in jewelry, lanterns, reliefs, vases, and sculptures, Greek sirens are actually half women and half birds.

Again, there is no unambiguous picture. Sometimes they are birds almost in their entirety, with only the human head. Other times the proportions are reversed: the mermaid has a woman’s face and body, with wide wings on her back. In the latter case, the resemblance to angels is very strong, except for the chicken feet. If you want to get a feel for this bird-footed angel, you can look at the intriguing statue of the Siren of Canosa, housed in the Archaeological Museum in Madrid.

Although they looked angelic, however, Greek sirens were not very peaceful. With their singing they lured sailors to their island, leading them to their deaths. It is Homer himself who describes the countless rotting corpses surrounding them.

To achieve this slaughter, we do not have to imagine hosts of feathered women: the Sirens of Odysseus’ island, in fact, were only two. They were also very touchy: according to the Orphic Argonautics (later than the Odyssey by about a millennium) one of the two Sirens, Parthenope, was so hurt by her failure with Odysseus that she decided to commit suicide, crashing on the rocks that would later see the stupendous city of Naples rise. The seas of Campania, by the way, were seen as the home of the Sirens: this is also why the Greeks who inhabited the Neapolitan coast worshipped them. For the Greeks, however, sirens were not only deadly enemies: the “feathered virgins,” in fact, also had the difficult task of consoling the dead by singing. That is why we often find depictions of mermaids on their graves.

Beautiful woman with long hair, instead of legs she has a sinuous fishtail. This is the iconography we are accustomed to, handed down from the stupendous European legends. Long before Andersen wrote the beautiful fairy tale of “The Little Mermaid,” in fact, oral tradition counted many stories chock-full of mermaids.

It is not clear when the transition between the feathered mermaid of the Greeks to the fish mermaid occurred, but this new image will triumph in all cultures, dominating in the collective imagination. Some Celtic legends even specify which species of fish the tail is from: it is the salmon.

Such is the case with the Mermaid Saint Li Ban of Irish tradition, who renounces her immortality to ascend into Christian heaven.

Another salmon mermaid is the Scottish Ceasg. In this case, legend has it that if caught, this can grant three wishes. Vladimir Propp, the great Russian anthropologist, noted that folk tales always had similar structures, with elements repeated in the oral traditions of all cultures. The three wishes, as well as the three tests to be passed, are among those elements.

I want to specify that mermaids are not the preserve of Celtic tradition: beautiful Italian, Spanish, and French legends tell of them. In particular, if you want to discover an extremely poetic fairy tale, you might be interested in the story of Skuma of Taranto. I discovered this legend while walking along the Apulian waterfront, coming across statues of mermaids, thus discovering the tale of Skuma (cf. foam), a beautiful maiden and her rich lover, full of twists, treasures and mermaids.

It was in Germany that I discovered a very eerie environment that was widespread throughout Renaissance Europe: the Wunderkammer, which can be translated into English as “Chamber of Wonders.” The Wunderkammer, typical of the courts, was a collection of curious and amazing objects. Archaeological finds, ancient objects and incredible animals found a place in the Chamber of Wonders of wealthy collectors.

Of course, there was no scientific rigor, and professional embalmers put together bodies of multiple animals to shape legendary beasts such as unicorns and dragons.

Of course, one of the highlights of the Wunderkammer was almost always the mermaid. Small and anthropomorphic, it had the appearance that today resembles the image of a finned alien.

How did they get it? By creatively stuffing the body of a race. This fish, when dried, takes on a truly eerie anthropomorphic appearance. Thus the bodies of small mummified mermaids appeared in European courts.

The mysteries of the sea are deep, and even today we have only marginal knowledge of the creatures that inhabit the deep. Clearly, mermaids are figments of fantasy and legends, but there have been many sightings in the past, with witnesses swearing they had seen them.

Among them is Christopher Columbus. In reporting this sighting of his, Columbus specified that they were not as beautiful as reported, however. How do you explain it? At sea, it’s easy to get suggestible. In all likelihood, the navigator spotted a walrus or similar aquatic mammal. This would also explain the aesthetic disappointment of Columbus.

In later centuries, there were many navigators who claimed to have sighted mermaids. The most recent case, in 2009, involved an Israeli town, with numerous witnesses swearing that they had observed real sirens near the coast. A rich prize was put up for grabs for those who brought firm evidence, but no one was ever able to go beyond mere testimony.

For those like me who love fantasy imagery, the mermaid represents a very intriguing and interesting creature. Often depicted as beautiful, she is even more unattainable than human maidens and even more mysterious. The mermaid symbolizes female sexual attraction and her power toward men.

In this regard we must remember that the mermaid populated the tales of sailors, men who were isolated from women for months at a time.

The mermaid was often depicted with a mirror in her hand, and this does not simply indicate her narcissism. As with the witch in Snow White, the mirror can symbolize a magical window to observe the world of the dead.

A symbol of beauty and the mysteries of the sea, the mermaid became the most common figurehead on European sailing ships. The figurehead is that wooden decoration that looks at the sea horizon from the bow of the ship. Some speculate that this fashion served to exorcise fear toward mermaids or was a kind of homage to keep them good.

Personally, I think this choice was more related to symbolic and aesthetic aspects, especially in the nineteenth century, the Romantic century. After all, what could be more romantic than a sailing ship plying the waves with a beautiful mermaid with long hair and beautiful breasts, braving the foams of the storm?

The symbol of the mermaid does not end there: widespread in Europe, her legend finds its way into the traditions of so many peoples of the sea, from Mexico to the Philippines.

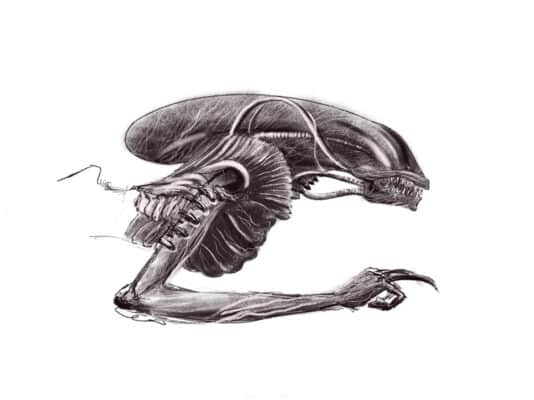

What is the Alien, or Xenomorph? Let’s find out its story, the meanings and symbols of the scariest predator in the universe. Anyone who has

The Ouroboros is an ancient and intriguing symbol that has fascinated cultures and philosophers for centuries. Depicted as a snake or a dragon biting its